Part III: The Miracle Windows: How Light and Beauty Preserved the Mythos of the Becket Miracles

Cult of Becket: Murder and Martyrdom, Case Study: The Medieval Pilgrim Panel, and Conclusion

CULT OF BECKET: MURDER AND MARTYRDOM

In medieval England (1100-1300), as the Crown and the Church were becoming more centralized, the relationship between the two became quite complicated and very interconnected. Robert Scully writes, “The Norman Conquest (1066) greatly accelerated this process of state building by the Anglo-Norman kings, and this same era witnessed the rising power and influence of the Papacy.”[1] As Church and State co-existed within their own established power, discord frequently occurred between them. When Henry II came to power in England in 1154, he quickly designated Thomas Becket, a close friend, to the position of Chancellor of England. Shortly after Becket became chancellor, the previous archbishop died, and King Henry appointed Becket to the now vacant position. Becket was aware of the “potential perils” of such a step, but, in the end, he agreed to accept the position and was consecrated in June 1162.[2]

Becket quickly let his devotion to himself and the Church overrule his devotion to the king. By 1164, he had resigned his position as chancellor, a move that removed some of the ties of power the king had over him. King Henry responded by issuing a declaration recognizing certain rights of the kingdom over the Church, including “prohibiting clergy from leaving England without the king’s permission.”[3] A permanent rift was born between the king and the archbishop. As the rift became more serious, Becket fled England for a period of exile that lasted six years. As an attempt was made to reconcile, he returned but continued his exertion of church power over the king, enraging the King even more.

During the evening hours of December 29, 1170, four knights murdered Archbishop Thomas Becket inside the cathedral, it is believed upon orders of the king. Both sides, Becket and King Henry, had their own allies, one side believing Becket “tempted his own death by usurping royal authority, while admirers of Becket thought he was a man of great spiritual courage.”[4] Whatever the opinions of both sides, it soon became apparent that the people of England were very upset over the murder of Becket. King Henry II himself, realizing the damage he had inflicted upon his friend and his own reign, began expressing deep regret and soon offered Thomas up as a saint and martyr, a sort of penitence and a relinquishment of his responsibility in the murder.

Immediately after the murder, miracles were witnessed among peasants outside the church and inside the cathedral at particular venerated spots, quickly rendering them as sacred. Robert Scully writes, “the miracles seemed to increase both numerically and geographically… first ‘about his tomb, then through the whole crypt, then the whole church, then all of Canterbury, then England, then France, Normandy, Germany, [and the] whole world.’”[5] Because of Becket’s death and the subsequent recorded miracles, in 1173 the archbishop was canonized as a saint by Pope Alexander III. The “Cult of Becket” was born.

As word of the miracles spread throughout England and the world, pilgrimages to Canterbury followed. The Church responded by opening the tomb of the saint in the crypt to the public, and word of miraculous healings continued to spread. Becket was revered by the peasant pilgrims, with the devotion to his sainthood spreading all the way up to the monarchy. This reverence lasted for many years and had a profound influence on the art and literature of the time, including the famous literary work by Geoffrey Chaucer, The Canterbury Tales.

The most spectacular art of the time was the stained glass made for Becket’s shrine in Trinity Chapel, where his body was translated from the crypt to the newly restored chapel after a devastating fire (d. 1174) that destroyed the eastern arm of the church. M.F. Hearn writes, “there is a certain mystery about the fire because it ostensibly was caused by sparks from a conflagration outside the southwestern corner of the close but without any damage to the western end of the church.”[6] Despite the origin of the fire, the crypt where Becket’s tomb was housed was not damaged; however, there was severe damage to the upper portion of the church. Plans for restoration and renovations were swiftly made, and over the next ten years, the plans were brought to fruition. After completion of the chapel and the translation of Becket’s body to the newly restored chapel, the shrine became the fourth sacred spot for the veneration of St. Thomas by the pilgrims. The first three sites sacred to Becket’s memory included the place of martyrdom, the tomb in the crypt of the original Trinity Chapel, and the altar in the original Trinity Chapel.[7]

CASE STUDY: THE MEDIEVAL PILGRIM PANEL

The Medieval Pilgrim Panel is a stained-glass window panel that is part of the installation of Window nV (Figure 2 and 3) in the North Ambulatory of Trinity Chapel at Canterbury Cathedral. The panel measures 30” high by 30” wide and depicts pilgrims on the road to Canterbury, some on horseback and some walking, including a man in front of the entourage with crutches looking back toward the pilgrims as they travel along the road. Rachel Koopmans, a medieval scholar that studies Canterbury stained glass, describes the narrative scene as “the foremost rider, clothed in blue, taking a ring off of his finger to give as alms to the disabled man.”[8]

The panel is understood to reference how the poor and disabled were able to fund their pilgrimages, through the generous alms of other pilgrims travelling to Canterbury. The idea of almsgiving by the medieval pilgrim had a pious motive rather than charity: “Almsgiving was a prime good work that earned the giver merit and shortened the ‘pains or purgatory.’”[9] Almsgiving relieved the immediate need of the poor but did not relieve poverty. Cathedrals of popular pilgrimages were a gathering place for the poor and needy. The scene of this panel would have been common and easily understood by the medieval pilgrim.

The panel is of a composite shape of a joined semicircle and triangle, the shape due to the central diamond-shaped panels that were installed above and below it. It is comprised of both mosaic stained glass, as well as the inclusion of glass-painting techniques employed during the Medieval period. The field (background) of the glass panel is mostly cobalt blue, while the clothing and other elements generally consist of blues, reds, and greens, primary colors. There are elements of white, including the horse, the paved road, and some of the garments. The figures appear in profile and are generally of a flat form, centrally fixed in the composition and taking up most of the panel space. Texture can be seen from the glass-painting technique known as the vitreous process, similar to modern enamelwork, as well as the lead glazing that holds the glass pieces in place. Texture is pronounced on the hair and beards of the figures, and details of texture can be seen on the pilgrims’ boots and in the folds of the garments. There is also traces of flashed glass, which produce the brilliant yellow color. This bright yellow is seen in the satchels, legs of some of the figures, and the saddle strap of the horse. It is known through research that some of the heads have been replaced, but most of the medieval glass is still intact.

EXCITING DISCOVERY

In 2018 onsite research was conducted of the Becket stained glass windows in the Trinity Chapel at Canterbury Cathedral.[10] The research revealed that the Medieval Pilgrim Panel is the earliest known depiction of the subject of pilgrims on the road to Canterbury. In order to determine what pieces were old and what were newer restorations, “every single piece of glass within the panel was examined, some 250 pieces, and it turned out that over 70 percent of the glass is medieval glass.”[11] The scene of the panel is of pilgrims who appear to be walking on a white road. There was an exciting discovery, however, when the panel was uninstalled for research. When the panel was removed from the window, the road was discovered to contain the inscription “PEREGRINI ST,” meaning “Pilgrims of the Saint” in Latin. This discovery was revealed by raking the panel with light in the conservation studio, something that could not have been seen while the panel was installed in its normal setting. Through research of Window nV, it was determined that it “was dedicated to events from the very beginning of Becket’s cult.”[12]

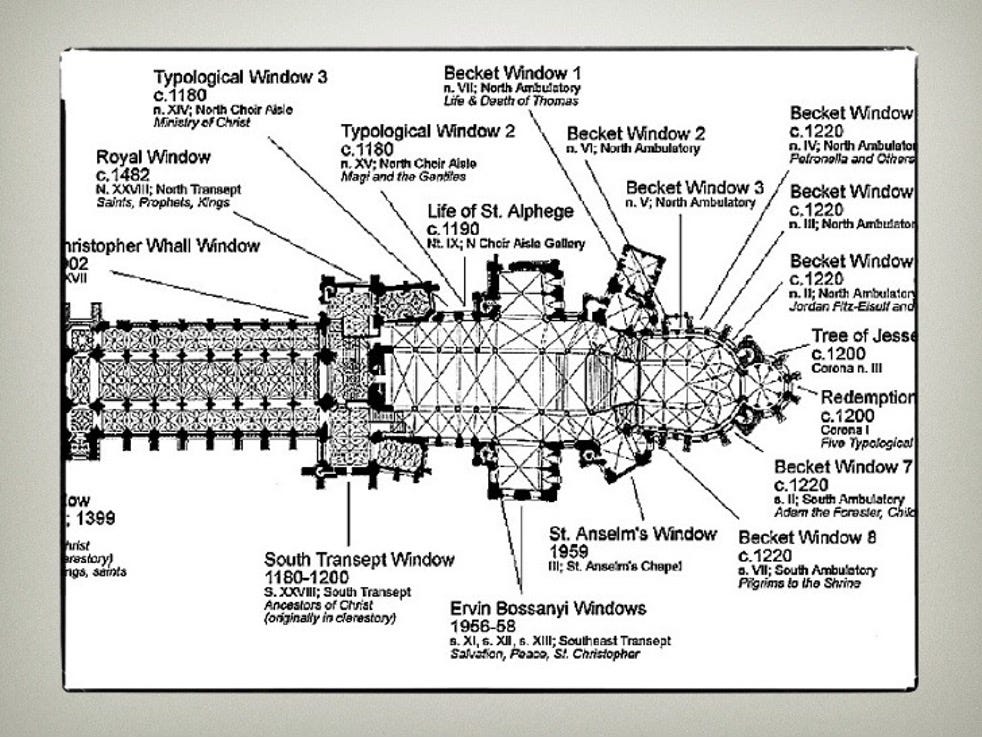

There are eight windows in Trinity Chapel related to Thomas Becket (see schematic at the top of this post.) Rachel Koopmans writes that “Windows nV, nIV and nII appear to be designed to picture defined historical phases of Becket’s cult.”[13] Window nV (the subject of this paper) contains the earliest examples of the Becket miracles and visions, and each panel tells a narrative story of the pilgrims from Becket’s cult. The medieval pilgrim would have understood the narrative stories of the window based on the sequence, although reading the inscriptions would have been difficult.

The narrative stories depicted in the panels are linked to writings by Benedict of Peterborough and William of Canterbury, together containing over 700 stories of miracles, written in about 1172-77. Some of the stories depicted in other panels surrounding the Medieval Pilgrim Panel include a man surrounded by three demons while he’s lying on a bed with a figure rushing to his aid (nV, CVMA 16); pilgrims lining up to have their ampullae filled “with the famous Becket blood and water relic”[14] (nV, CVMA 14); and a panel depicting a sleeping Steven, a priest, who is visited by a man who tells him of “the miraculous power of the blood and water relic”[15] (nV, CVMA 6.)

The discovery of a panel in Canterbury Cathedral consisting of mostly medieval glass is an important discovery for art historical analysis because it helps us understand the pilgrims’ motivation to travel to Canterbury, as well as the effect stained glass had on the visual perception of the pilgrim, translated as the holy light of God.

CONCLUSION

Stained glass was relevant in its time for the role it played in beauty, light, and the enlightenment of scripture for the pilgrim. It is relevant today because, as we study its cultural meaning during the period of its creation, we understand and experience it more reverently in our time. The Church of the time understood the power of light and narrative stories and was successful in preserving the mythos of St. Thomas by the use of light and story. In our modern time, we have lost the sense of the miracle of light. The Medieval period is not truly understood without viewing its objects through the darkness of the time. Considering the glass through the viewpoint of darkness actually enlightens the viewer to the visual perception of the pilgrims of Canterbury. It is also critical to ask the question: Who was making the art and why? The patrons of art were the monarchy and the Church, and both were involved in power struggles to keep control of their own domain. The pilgrim was substantially affected by these power plays. Even if they were unaware, these struggles affected their lives physically and spiritually.

The story of Thomas Becket is a prime example of this struggle between Church and State. Becket’s murder was the result of a power play; his martyrdom was encouraged by the king to preserve his reign after witnessing the reverent response of Becket by the people; and the resulting beauty the windows provided from this tragic event was encouraged by both sides, the Church and the monarchy. The pilgrim, although affected adversely by the murder, also benefited from the light and stories of miracles that would not have happened without the power struggle. Considering events in our own time, we can see how our lives are affected sometimes adversely and sometimes favorably by the power struggles of leaders. Viewing the art of our time, it is evident that works are often constructed from more than just the desire of aesthetic beauty. The motivation can be social or political and can affect the psyche of the population by its beauty or by the message it prompts us to consider. Understanding the motivation behind objects such as the Miracle Windows at Canterbury reveal social constructs that teach us about the historical past while informing or providing warnings for our present. This is the beauty found in understanding the Miracle Windows of Canterbury Cathedral: the art of the windows communicated meaning to the lives of the pilgrims in their own time, and there is value to us in our time as we consider their beauty, story, and lessons for us.

Fascinating 😍