Part II: The Impact of French Huguenot Artisans on English Cosmopolitanism During the Reign of William and Mary (1688-1702)

Case Study: English Baroque Designer, Daniel Marot (1661-1752)

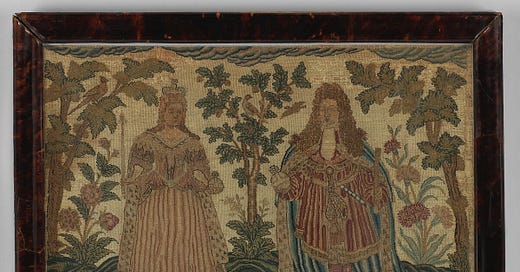

Artist Unknown, Portrait of William and Mary, Silk Thread on Possibly Linen, Late-Seventeenth to Early-Eighteenth Century, The Met, New York, No. 39.13.9

Political and Aesthetic Value: William and Mary Use Personal Symbolism and Style to Gain Power and Influence

In order to understand the political and aesthetic value that is the focus of this essay, it is important to understand why certain objects of the period held value to society and how these values affected interactions between William and Mary’s subjects. Central to the design plan of a titled nobleman’s English country house, as well as to his chances of securing a visit by the Court, was the state apartment. Usually comprised of three chambers, the state apartment included an antechamber (a gathering room outside of a larger room, common in large homes and palaces), the bedchamber, and a closet. The bedchamber was not, however, for everyday use by the family. It was reserved for distinguished visitors. The foremost purpose was anticipation of a visit by the king or queen. Secondly, for formal family receptions following the marriage of an heir or heiress, the birth of an heir, or used for the death of a senior relative as they would lie in state.1

The most expensive object in the state apartment was the bedstead. Of all English Baroque furniture, the state bedstead was the showpiece. No expense was spared on the fabrics and trimmings used for the upholstery, the elaborate carvings for the frame, or the magnificent testers. One notable example is the Melville Bed (1697).

Click here for to view the Melville Bed, © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Object Study 1: The Melville Bed

The Melville Bed, believed to be designed by Daniel Marot and commissioned by George Melville, 1st Earl of Melville (c. 1634-1707), for the state bedroom at Melville House in Fife, Scotland, is a masterful example of a state bedstead. The Melville Bed, now housed in the Victoria & Albert Museum in London, was used as a status symbol by Melville to showcase his service as a representative of William III in Scotland. Melville served as the king’s secretary of state (1689-1691), keeper of the Privy Seal (from 1691), and President of the Council (from 1696).2 The use of the bedstead to elevate the status of the Earl while solidifying the power of the king and queen in Scotland cannot go without mention. Although Melville used this state bed as a material object to showcase his own power, this commissioned bed reveals that the king allowed his personal architect and designer, Daniel Marot, to design objects that solidified his power throughout the kingdom through the homes of his noble subjects.

The Melville Bed is a marvel in its design and structure with craftsmanship of intricate detail. Nearly the entire bed is covered with fabric. The wood posts are upholstered, as well as the carving on the headboard, all glued with precision and skilled upholstery cutwork. Only a master upholsterer would have the skills required to cover carvings and posts in this manner. A description of the piece reveals the extensive detail Marot used in his design, showcasing the classic baroque style of the period, by using carved ornate scrollwork and curved lines. A description of the details explains the structure of the bed as well as the upholstery:

The bedstead consists of an oak bedstock with four oak posts secured to the rails with bolts... the frame of the bed retains its original ropes... which are attached to the side and foot stock rails and a tension baton at the head of the bed... The top of each post has two iron hooks to secure the curtain rods. The top of the posts hold iron spikes which secure the tester and cornice. Each of the posts have silk damask covers lined with linen. The pine cornice frame also slots over the spikes above the tester sub-frame and is separated from the latter by oak spacers... The tester cloth is of a different Chinese silk to the bed curtain linings and counterpane... The outer cornice of the upper framework is covered with crimson velvet with crimson fringe... The silk inner upper valances are attached to the inside of the tester frame... The headboard similarly covered with cream silk and embellished with crimson silk braid and fringe supports a cresting of pierced acanthus plumage, and is embellished with a joint monogram of George, First Earl of Melville, and his wife, Catherine... There are two foot curtains and two head curtains... made of five panels of velvet... The coverlet, a remarkable survival, is of silk damask embroidered with crimson braid and fringe... The central cartouche frames the Earl’s monogram beneath an Earl’s coronet with a pendant of simulated tasseled fringe embroidered in crimson braid.3

Marot created etchings of his designs as examples of his work. Although the creation date of his pattern designs is still under some debate, the etchings were published in a pattern book he used to market himself for later work. The etchings contain several designs for bedsteads in their entirety, including the upholstery, not just the carving and framework.

The etchings are a good source and record of furnishings of the Baroque era in England and provide the provenance for Marot as the designer. However, it is important to note a counterpoint made by Adam Bowett in his journal article, “The Engravings of Daniel Marot,” where Bowett’s research answers the “sequence of publication based on surviving original copies of Marot’s works.”4 Bowett questions whether Marot is due the credit he is frequently given for designs in this period because some of the dates of the etchings fail to line up with the timing of the final products themselves. However, he does concede that, “This does not, of course, invalidate the argument that it was Marot himself, rather than his publication, who was the agent of innovation and change.”5 From the research reviewed for this essay, it is likely the case that the delay in Marot publishing his designs and body of work does not mean his ideas were not produced in real time. It could easily be argued that his work for the king and other English patrons was so successful that he was encouraged professionally and personally to publish his designs at a later date. However, further study of Marot’s designs and matching the designs with historic pieces would be a useful study to answer these questions.

Another bed similar to the Melville Bed, the State Bed from Hampton Court, Herefordshire (c. 1698), was designed by Marot and made for William’s fellow friend and courtier, Thomas Baron Coningsby (1656-1729), First Earl to Coningsby. Coningsby commissioned one bed for the state apartment in his home and another for his personal use.6 There is a record of King William III actually staying in the state apartment, published in an article in the Leominster Guide of 1808:

One of the apartments, which is furnished with crimson damask hangings and a bed and canopy of the same, remains in precisely the same state as when used by William III who here visited Thomas Baron Coningsby... 7

The bedstead made for Coningsby’s personal use was upholstered with blue silk damask. The bedstead was discussed in an article in Country Life magazine in 1911, written by Avary Tipping after the discovery of the bed in an attic at Hampton Court, Herefordshire. Tipping wrote, “So fine a bed of the Marot type in such unusually perfect state is rare indeed.”8

State apartments were showcases of family power and connection to the Court, and the bedstead was the primary showpiece. They were elaborate displays of loyalty to the king and power of the family lineage, as they were used for the birth of heirs, consummation of wedding vows for newly-married heirs and heiresses, and for funerary purposes of the senior relatives of the household. State bedsteads are excellent object studies for exploring the English Baroque period, and Daniel Marot’s designs are essential for understanding the shift in style from hard furnishings to soft.

Click here to view the Delftware Garden Pot, © National Trust Collections

Object Study 2: Delftware Orange Tree Pot

Of all the tools used by William and Mary to visually symbolize their image, the use of delftware permeated their culture the most. Mary commissioned delftware pieces for both palaces in the Netherlands and England, notably, the Palace at Hampton Court. However, she also commissioned pieces for her personal spaces, including a private out-building, similar to the summer kitchens of other Orange princesses known as the “dairy,” within the Water Gallery at Hampton Court. Mary re-tiled her summer space with Delft tile designed by Marot (produced in the Grieksche A factory), where she also stored other pieces of her Delft collection. The commissioned tiles referenced Orange-Nassau individuals explicitly.9 One example depicts the the image of William as a Roman Emperor with his crowned initials W.R. (William Rex.) Mary also commissioned many vases, milk pans, and garden pots with symbolic imagery, where “the influence of court-appointed designer Daniel Marot...can clearly be seen in this ‘Royal Blue.’10 There were mass-produced ceramics such as plates and teapots with orange symbols with portraits of the king and queen, their initials, and some with fruit-bearing orange trees. Not only did English subjects show their support through the use of delftware, but “Dutch citizens showed their support for the House of Orange-Nassau on earthenware.”11 As the monarchy grew more popular and Mary used more symbolic delftware, other companies commercialized the pottery for uses beyond just the home of the king and queen. In doing so, these objects performed important work for the House, retaining prominence for their leadership in often politically fraught times.12

Both William and Mary had a keen interest in gardening. One remarkable example is while William was traveling toward London to take over rule of England, he made a stop to visit a garden project he had been reading about on the edge of St. James Park.13 Mary also created an orangery to grow tropical plants and citrus trees. They both had a hand in creating grand gardens at their palaces in Holland and by importing the Dutch style to their gardens in England, using Marot as the designer of the garden parterres at Hampton Court Palace.

Delftware is a tin-glazed earthenware that is hand-painted with blue on a white background. The origin of the name “delftware” comes from the city in the Netherlands where it was first created, Delft. The factory that was used to make the pottery for William and Mary was De Grieksche A (Greek A) factory. The artist and craftsman was often Adrianus Kocx, and the designer of the pottery for William and Mary was Daniel Marot.

In reviewing the importance of gardening and out-spaces for William and Mary, a pertinent example of one of the objects they introduced is the orange tree pot that is now held in the National Trust Collection in the museum of the country house of Erddig, Wrexham, England. The significance of the Erddig Garden Pot is in the symbolism it displays. The pot stands in campana form and approximately 26 inches in height and 19 inches in width. The pot is made of tin-glazed earthenware with cobalt blue and manganese black details. It has a detachable flared rim in the form of a crown, resting on a lower rim that is painted with floral decoration, and includes moulded handles on each side. The central body of the pot is decorated “with the royal arms of William III, enclosed by the garter, and surmounted by a crown moulded in relief. The reverse has the monarchs joint cipher ‘WMRR’ (Wilhelmus Maria Rex Regina) strategically placed with the Stuart arms,” also surmounted by a crown in molded relief.14 The lower portion is decorated with horizontal beaded false gadroons and is sitting on a base with four moulded legs in relief with shell and scroll upper parts, terminating with paw feet, and displaying a scallop shell in relief between each leg. The piece has a mark of AK, which is the mark of the Grieksche A factory, but it is likely the mark of the craftsman, Adrianus Kocx, who later owned the factory.

As William and Mary were building their power and influence, another parallel shift occurred through installations of new furniture and decorative art in their palaces, especially at Hampton Court. Daniel Marot, the cosmopolitan designer, made a lasting impression of William and Mary on their subjects, while also introducing the baroque style of furniture and decorative arts to England.

Click here to view the Carved Walnut Dining Chairs, © National Trust Collections

Object Study 3: Carved Walnut Dining Chairs - Marot as the Originator of English Style

The genius of Marot was the detail of his designs and his “ability to adapt the French style for the Dutch interior, using a unique and luxurious baroque expression.”15 His work with William and Mary corresponded with a major change of interior fashion in England. Marot’s design philosophy of using soft furnishings represented the fall of the medieval style of the Jacobean and Carolean era, generally made of oak, dark and heavyset in appearance, to a lighter, more airy design of Dutch/Flemish influence that was crafted in walnut and included a curved aesthetic, highly decorative forms, and with a focus on comfort instead of rigidity. Marot “typified the swing of British taste away from provincialism toward greater luxury and ornateness.”16

It is no surprise that Marot’s contemporary designs were unique since he worked within two of the most influential countries of the art world during his life, France and the Netherlands. With the benefit of both his former French citizenship and his new Dutch citizenship, and while working under some of Continental Europe’s master craftsmen, Marot’s cosmopolitan upbringing bled through to his designs. Marot was able to blend the opulence of French design with the pristine detail of the Dutch, creating a new style of his own. Marot was a student of of his uncle, Pierre Gole’s, skilled inlay marquetry work, and he certainly benefited from exposure to this mastery. His chair designs, for example, transformed the English look from the heavy block oak form to intricately carved chairs with elongated backs and upholstered seats. He substituted rigidity for comfort by masterfully using upholstery. He introduced the cross X-stretcher with turned legs and bun feet to England, which is still the hallmark of furniture from the William and Mary period today.

The third notable material object of this study is a set of six walnut dining chairs held in trust at the National Trust Collections at Sudbury Hall in Derbyshire, England. The high-back walnut dining chairs have a carved trophy crest in the form of a leaf, pierced carved back splats of scrolls, foliate and basket-work design, flanked by two turned outer posts that are both surmounted with a turned finial. The chairs have an upholstered cushion of crimson velvet, turned legs with fluted turnings that terminate with fluted ball feet. The legs are connected with a cross X-stretcher, surmounted in the center with a turned and fluted finial. The chairs reveal Marot’s design style distinctly, as they have heavily carved back splats, the X-stretcher, and an upholstered cushion, hallmarks of the transitional style Marot introduced to England.

Chairs of this style would have been crafted for aristocratic homes that were embracing the Dutch style of the new king and queen and would also have been used to entertain nobility. Marot’s design oeuvre also included tapestries with symbols like the joint cipher of the king and queen, as well as architectural wall panels with carved scenes and elaborate trimmings, gueridons, and fireplaces. Marot’s work involved any furnishing related to the interior space, including architectural wall elements, furniture, and soft furnishings. Marot is likely the first designer to create complete room interiors, furniture, fittings, and upholstery.17 Few works today are attached to Marot’s name with certainty; however, with the publishing of his engravings, his designs continued to be copied and studied as inspiration for designers, architects, cabinetmakers, and craftsmen.

Daniel Marot’s engravings were arranged as books, also called livres, and were “probably sold as individual livres or as collected editions, and at least three were published during his lifetime.”18 Marot is best known through the publishing of his engravings, which has permitted art historians to match his designs with material objects from the English Baroque period, establishing provenance for many works held in museums today “in the style of Marot.”19

Conclusion

Material objects like the Melville Bed, the Erddig Garden Pot, and the Set of Six Walnut Dining Chairs reveal the desire of the monarchy to establish their name and kingdom in England using Dutch style and grand elements designed by Daniel Marot. The king and queen recognized the importance of establishing their power and influence through material objects, a practice developed early in their lives through family influence. Another material object that is a worthy example for later study is the use of portraiture by the joint monarchy to establish power. William III’s mother and grandmother used portraiture to install the presence of William among the English court even when he was a child, as well as throughout Continental Europe in the homes of other Dutch relatives. William later continued the tradition of using portraiture to establish his own image in the international context of elite rule.20

William signaled his marital aspirations for his future wife, Mary, in a gift to his uncle, King Charles II, who was also Mary’s uncle and as king had charge over her life. Mary was in line for the throne of England in succession from Charles II, that would then pass to her father, James II, before falling to her. William’s use of images was rewarded, in that it contributed to his eventual marriage to Mary. William and Mary both used portraiture after their marriage to continue symbolizing their image as joint monarchs. There were also portraits commissioned by affiliates of the House so these relatives could “flag their allegiance by their artistic commissions.”21 The use of material objects influenced and shaped the culture around William and Mary that included the entire country of England and Continental Europe.

But with this great shift in history and design in England, there is not a full compilation of the life and works of Daniel Marot. Several journals and books mention his life, designs, and work, but nothing in the form of a biography (at least in English) has been located during this research. The influence Daniel Marot had on architecture, interiors, the gardens of England, the Netherlands, and Continental Europe deserves a compilation to aid in the study of this period of history and to assist in the preservation of objects held in museums all over the world bearing his name. Daniel Marot was responsible for influencing an important transition in furniture history. A full compilation of his life and work, including a comparative analysis of the designs he left behind, would benefit those studying this period in history for years to come.

This is fantastic, Tiffany. So much to think about here.